Unlike my personal website where I publish pages that are really in progress — with TODOs floating around, fragmentary thoughts, and much unpolish — any given in progress page on this ministry website is really only in progress insofar as I have not finished writing all the content that I expect to be eventually located on the page. That is to say, everything that is published on the page is already complete, edited, and checked-over for accuracy and correctness, but there is still more planned writing on the page to be completed.

I'm an outliner when I write, so how this plays out in practice is that I will fill in the outline skeleton (as displayed in the table of contents) with content over time, until the whole page is eventually complete.

Tentative Eventual Structure For This Page

Pre-optimization Considerations

Reasons Why You Should Optimize

- Reduced Typing Effort

- Reduced Risk of RSI

- Increased Typing Speed

Reasons Why You Should Not Optimize

- Priorities

- You May Type Too Little For Optimization/Switching To Be Worth It

- You May Be Better Served By Learning Stenography

- The Difficulty of Retraining Your Fingers

- QWERTY’s Ubiquitousness

- The Animosity of Others

- Most Speed Considerations Are Layout Agnostic

People Who Should Always Learn An Optimized Layout

Prior Studies of Keyboard Layouts

Optimization Considerations

Differences in Hand Morphology

- My Hand Morphology

Differences in Optimization Goals (speed vs ergonomics)

- My Optimization Goals (balance)

Differences in Textual Corpus

- My Textual Corpus (Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Markdown, Org, LaTeX, programming, number entry)

The Unavoidability of Opportunity Cost: Coming to an “Optimal Compromise”

The Danger of Perfectionism

Character Layout Design Factors

- Finger Travel Distance

- Same Finger

- Indirect Same Finger

- Shift Same Finger

- Hand Alternation

- Two Hand Alternation

- Inward Motion Frequency

- Outward Motion Frequency

- Inward/Outward Motion Ratio

- Inward Roll Frequency

- Outward Roll Frequency

- Inward/Outward Roll Ratio

- Roll Conformity to Standards Based Upon Hand Physiology and Subjective Analysis

- Vertical Hand Shift (“Row Jumping”)

- Number of Movements Between Rows

- Horizontal Hand Shift (“Column Jumping”)

- Number of Movements Between Columns

- Finger Load Conformity to Standards Based on Hand Physiology and Subjective Analysis

- Hand Balance

- Adjacency

- Shift Adjacency

- Home Position %

- Favorable Position %

- Index Extension %

- Pinky Extension %

Weighting of Character Layout Design Variables

Comparison Methods

- Layouts: Numerical Scores Based on Percentage-Based Weighting of Variables

- Individual Factors: Percent Difference Between Layouts

- Individual Factors: Normalization by Best Performing Layout

General Approaches: Specialization vs. Jack of All Trades

- Imperfect Knowledge of Variable Importance in General

- Imperfect Knowledge of Variable Importance with Respect to Individual Differences

Preliminary Design Considerations

- Additional Keys vs. Layers

- The Most Efficient Methods of Accessing Layers: Leader Keys vs. Modifier Keys

- The Most Efficient Keys to Access Layers: Thumb Keys vs. Finger Keys

- Key Priority for a simple 40-Key Layout

- Key Priority for a Multilayer 40-Key Layout

- Subjective Key Weighting for a simple 40-Key Layout

- Subjective Key Weighting for a Multilayer 40-Key Layout

- Dual Use: Modifiers on the Home Row

Key Scope: Usage Context Driving Availability

- Importance

- The Accessibility of Control Keys Across Layers

- The Accessibility of Modifier Keys Across Layers

- Space

- Esc

Key Clustering Patterns

- Importance

- Numbers

- Navigation/Editing

- Mousing

Grouping and Consistency: Why Computer Optimized Layouts May Not Always Be Superior

- A Brief Discussion of Human Cognition

- “Chunking”

- Key Frequency Considerations

Base Layer

- Reasons for Including All the Letters on the Base Layer

- Reasons for Keeping E off of the Thumbs

A Comparison of Letter Layers

- HIEAM as Superior Choice

Determining Which Punctuation Keys Should Go on the Base Layer

Determining How to Lay Out the Punctuation Keys on the Base Layer

Placement of the Space Key

Placement and Usage of the Shift Key

Placement of the hotstring key

Entering Commands

Entering Vim Normal Mode

Entering Specialized Modes (e.g., Greek, Hebrew, logic)

Caveats

- Character frequencies are based on typing out all words; do not take into account text expansion/briefs

- Writing Corpuses Change Over Time

- Individual Physiological Factors Change Over Time (e.g., Arthritis)

Pre-optimization Considerations

Before you spend time optimizing the character layout of your keyboard, you need to first make sure that you have a well-designed keyboard, and that your work environment is setup properly. Failing to account for these things (which are really more important), no matter how good your character layout ends up being, will put you at a much higher risk for Repetitive Stress Injury (RSI) and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS).

Optimizing the character layout of your keyboard without first dealing with your workstation ergonomics is like fixing a small leak in a ship while ignoring the gaping hole in the hull — any benefit you gain here will be vastly overshadowed by the gains from improving these other areas. Again, let me repeat myself, focusing on the character layout before settling these other matters is not wise, and I suggest you take some time to fix any deficiencies in your current equipment/habits before continuing.

Reasons Why You Should Optimize

Reduced Typing Effort

Far and away the biggest benefit optimized keyboard layouts give is a greatly reduced overall typing effort. As will be discussed below, optimized layouts significantly reduce the amount of distance your fingers need to travel by putting frequently used keys in favorable positions (like the home row), and balance finger and hand distribution so that effort is spread out. They also strive to make frequent two-letter combinations (called digrams) and three-letter combinations (called trigrams) easy to type: th, he, tha, ion, and so forth.

It is perhaps easiest to demonstrate the benefits of optimized layouts by counterexample: using “problem words” from QWERTY.

- On QWERTY try typing the word “stewardesses.” It should be immediately obvious what the problem here is: your left hand does all the work while your right hand just sits there doing nothing!

- Now try typing the word “minimum.” Aside from being another example of one hand doing all the work, QWERTY’s minimum has additional problems: you have to jump over the home row to get from M and N to I and U, and you have to use the same finger to type M and U in succession. As variables, these are usually called “row jumping” (or “hurdling”) and “same-finger”, respectively, and most optimized layouts try to minimize them as much as possible.

Basically, optimized layouts have less words like QWERTY’s “stewardesses” and “minimum” – words that are hard to type, split the load unequally among fingers and/or hands, require your fingers to travel further, require row jumps, etc. Consequently, typing is less effortful on optimized layouts.

Reduced Risk of RSI

Theoretically, the reduced overall effort needed to type on an optimized layout could lead to a delay in onset and/or remission of symptoms for those suffering from RSI, but I am not aware of any rigorous scholarship on the subject (though anecdotal success stories abound, they are not verifiable, and may be demonstrating the power of the placebo effect rather than the power of optimized keyboard layouts). On the other hand, it would make sense if less effort over time led to less “repetitive stress” overall (even if science hasn’t verified this yet), so giving it a shot may still be worth it.

It is once more worth pointing out that a well-designed keyboard and proper workstation ergonomics are much more important than a character layout ever will be on this front, so if you don’t have these things in order, an optimized keyboard layout won’t save you from RSI.

Increased Typing Speed

While this is perhaps the most controversial of the benefits (and is yet to be verified in a rigorous way, like RSI reduction above), there is a theoretical basis for faster typing on optimized layouts. For example:

- Optimized layouts require less overall finger travel distance, with most of the most frequent letters and combinations requiring no movement from the home row. Less required movement ought to lead to faster speeds, all other things being equal.

- Optimized layouts have higher hand alternation than QWERTY. Hand alternation makes it easier to line up the next letter when typing the previous one, since your fingers on the next-letter hand will not be out of position from typing letters on the top or bottom rows. (Cf. the QWERTY digraphs “he” and “in”. For the former – an example of hand alternation – E can easily be lined up while you are pressing the H key since they are on different hands despite being on different rows. For the latter, it is harder to line up N when you are pressing I since I is on the top row of the right hand and N is on the bottom row of the right hand). This too should theoretically lead to faster speeds.

- Optimized layouts have less same-finger (as in QWERTY “fr” or “ed”). It is not possible to line up subsequent letters in any way for same-finger digraphs, making them the slowest letter combinations. It follows then that layouts with less same-finger combinations will enable faster typing.

I’m sure there are other such features that could be mentioned in support of optimized layouts being faster (i.e., this list is not intended to be comprehensive); however, until rigorous studies are done, all of this is theoretical. The effects mentioned above are going to be much less significant than practice overall – which is why some QWERTY typists like Sean Wrona will destroy the vast majority of people who type on optimized layouts.

Reasons Why You Should Not Optimize

Priorities

Please have a look at this page.

Keyboard layout optimization must be taken as an investment of lower marginal benefit than many things before it. It is a worthy investment, but it is not the worthiest of your consideration unless several more important things have been taken care of beforehand.

I would encourage you to go through that link and make sure you have those things in good order before you even consider sinking in time on the keyboard optimization front.

You May Type Too Little For Optimization/Switching To Be Worth It

If you already touch type QWERTY, and you do not type very much in your profession or hobbies outside of your profession, keyboard layout optimization will never be worth your while. This goes doubly for those of you already using a better layout like Dvorak, Colemak, or Workman. You will never make up the time you spend making a more efficient layout for your use case and learning it because you will never type enough for the advantages to be realized. This will be discussed more extensively in some of the sections below, but suffice it to say that the opportunity cost involved is great enough that most people probably shouldn’t bother. There are some very zealous people that try to “sell” the idea of optimized keyboard layouts far more than what the data allows. They are objectively better. But not worth 50+ hours of practice to switch better. (Unless you are really worried about RSI).

You May Be Better Served By Learning Stenography

Steno is unarguably faster than typing, and certain people would be better served learning stenography instead of a more optimized keyboard layout.

TODO: Elaborate

The Difficulty of Retraining Your Fingers

The adjustment period whe switching from one layout to another will be on the order of weeks not days, and recovering your old speed will take time. If the switch were easy or effortless, QWERTY would have ceased to exist long ago. As it is, however, you will be reduced to single digit WPMs for the first little bit, and your fingers will disobey you — you will have to rewire the neural connections in your brain that correspond to what we call “muscle memory.” If you have any sort of time-sensitive full-time occupation that forces you maintain your QWERTY skills (i.e., you can’t afford to go cold turkey and immerse yourself), it’s even harder because you’ll experience proactive interference from already having QWERTY in muscle memory. That is to say, instead of “unlearning” QWERTY when you learn your other layout (replacing the old muscle memory with new muscle memory), the old muscle memory that you need to keep around will inhibit effective acquisition of the new muscle memory.

Depending on your dedication and consistency in practice, getting back to your previous speed can take anywhere from a few weeks to a few months. Poor discipline and lack of self-control can even push this from “difficult” to “impossible.” I would suggest that you not waste your time if you are not willing or able to put in the work necessary to be successful.

QWERTY’s Ubiquitousness

As mentioned above, holding QWERTY in muscle memory when learning a new layout results in proactive interference. For most people, the flipside, called retroactive interference, also holds true. Learning another layout will typically result in a loss of QWERTY speed because more errors are made — when you are trying to type a letter, your finger “forgets” that you are typing QWERTY, and instead presses the key for the letter on your other layout. While this is a problem for everyone, some people, through practice, have been able to keep high speeds on two different layouts simultaneously (e.g., Dvorak and QWERTY). Learning two layouts that are more similar to each other (like QWERTY and Colemak) is more likely to result in retroactive interference (just how learning Italian if you speak Spanish is more likely to mess with your Spanish than if you learn German), while using different physical keyboards for different character layouts (e.g., using Dvorak on a Kinesis Advantage and QWERTY on normal row-staggered keyboards) can help prevent retroactive interference.

The upshot of all this is that most people don’t continue to type with two different layouts in the long run — in other words, learning an optimized layout generally means you lose your QWERTY proficiency. The “problem” with this, of course, is that the rest of the world is designed for QWERTY and expects you to use it.

Not being able to touch-type QWERTY means your productivity will take a hit whenever you have to type on it for some reason (e.g., working on someone else’s computer or taking the GRE). You will also have to contend with keyoard shortcuts designed for QWERTY (such as Ctrl-Z, CTRL-X, CTRL-C, and Ctrl-V), which usually only prove to be problematic in those programs that don’t let you change them (boo on them). These are unavoidable consequences that you will face because QWERTY has become the expected layout in our society – if you find them unacceptable, stick with QWERTY.

The Animosity of Others

Certain people get rather worked up any time someone mentions a layout other than QWERTY. My best guess is that this is because the superior efficiency of people who type on other layouts is a direct challenge to their self-perception as competent, effective workers. It’s also possible that their defensiveness is a manifestation of the sunk cost fallacy: having spent a significant amount of time learning to touch-type QWERTY, they don’t want to admit that they picked a bad layout. There is also likely a degree of choice-supportive bias: similar to how people evangelize the make and model of the new car they bought to help convince themselves it was worth it, people are more likely to evangelize QWERTY after deciding to make it their keyboard layout.

Whatever their motivations, some people will challenge your decision to use a layout other than QWERTY. If you are not the type of person that’s cool taking heat for being different or constantly having to explain yourself, you may want to think twice about using a layout other than QWERTY.

(Note: you will encounter a larger group of people that is not actively antogonistic but merely confused as to why you find using another layout necessary or prudent. By and large, people in this group are happy shrugging and letting you do your thing if that’s what you want – but they may still give you weird looks. YMMV)

Most Speed Considerations Are Layout Agnostic

There is a very real possibility if you switch that the time lost in getting back up to speed would have been better spent honing your mastery of whatever layout you do currently use, because most of the ways you can accelerate your typing don’t depend on your layout. In other words, it would probably be better for you to spend a couple months increasing your QWERTY speed from 70 WPM to 100 WPM than getting up to 70 WPM on another layout.

Practice

There is no magic here. Optimizing your layout won’t immediately make you a faster typist, though it certainly has the potential to eventually. The thing that will make you a faster typist is practicing a layout until you breathe it and you dream about it. This is like every single other skill in existence; the more you practice, the better you get.

I want to here emphasize that not all practice is equal. Practice does not make perfect. Practice makes permanent (or, alternatively, “perfect practice makes perfect”). Because we tend to type a great deal in our day to day lives, there is a danger of just going on autopilot and plateauing. Whether or not you decide to continue on in this process, I can recommend that you pick up typing not as something one merely does, but as something one studies and perfects over time.

Practice the most common digrams and trigrams in English (or your native language if not English). Lists can be found here, here, and elsewhere through a simple Google search. If you consciously train yourself to type sequences rather than letters, your speed will increase at a much faster rate.

To extend this concept even further, you should drill with this list or this list, which have the most common words in English listed out by frequency. It does you little good to type uncommon or unusual words at a high speed because they compose a small portion of what you type (e.g., typing “zyzzyva” fast does you no good because genuses of weevils don’t come up in normal conversation). Getting very fast at words like “the”, “and”, “that” and so forth, however, will dramatically increase your speed because these words compose a large percentage of everything we type.

Targeting Weaknesses

If you haven’t used Amphetype before, you should try it. It is a program that lets you track what things you type fast and what things you type slow (among other things).

A common mistake many people make when learning skills is treating all practice as equally helpful. This is objectively false. As anyone who has ever learned a musical instrument can tell you, you improve much faster if you practice the hard sections in a piece rather than playing it all the way through a bunch of times. (Even though this is much less fun, you improve more). I call this “targeting weaknesses.” If you target your weaknesses, you may improve many times faster than someone who thinks that all practice is basically the same.

(Note: this same principle carries over into knowledge acquisition as well – study what you don’t know, not what you do).

Text Expansion

If you really want to ramp up the speed, you should use text expansion to abbreviate at least the first couple hundred most common words and phrases in English, making, for example, “and” just “n”, “I want to” just “iwt”, and so on. By doing this alone, you can cut down on how many keys you have to physically press down by a huge percentage (at least for prose). You can actually do the same thing for common code constructs (e.g., the basic syntax of a for loop in Python), email signatures, and really anything else you can think of. Since I’m on Windows, I personally use AutoHotkey for this purpose, but there are plenty of options for this sort of thing. If your keyboard supports it, you may be able to do text expansion on the firmware level, making it operating system and device agnostic.

Just like normal typing, you’ll need to practice this intentionally to get results, retraining your hands to type “n” every time your brain thinks “and”. You’ll also want to create a “theory” for your abbreviations, and come up with some patterns to reuse as your list grows (e.g., using consistent letter sequences for phrase enders — “iwt” for “I want to”, “hwt” for “he wants to”, “swt” for “she wants to”, etc.). A working knowledge of a brief-heavy stenographic theory will help you here.

Number and Symbol Layers

You can create layers for numbers and/or symbols while still using QWERTY for letters. These additional layers have nothing to do with letter layouts, but will still increase your speed – especially if you are a programmer or deal with information that includes lots of numbers.

Conclusion

Most speed considerations are layout agnostic. If you are already a sufficiently fast typist with another layout, the time spent regaining your old speed on another layout would probably be better spent beefing up your current toolkit and optimizing other parts of your typing. No matter what you do, dedicated intentional practice can significantly improve your typing, and you shouldn’t switch without first considering if it is really the most rational decision under your circumstances.

People Who Should Always Learn An Optimized Layout

If you hunt-and-peck, it’s going to take you a while to learn how to touch type anyway, so you may as well do it right the first time. Learning how to touch type is really a very important skill since a) it’s faster, b) you can look at other things (like the screen) when you type, and c) you make less mistakes. The good news for you is that you should be able to get up to 20 WPM or so in a weekend, which shouldn’t be all that much slower than your normal hunt-and-peck speed (i.e., you won’t have quite the same magnitude of productivity loss that touch-typists switching will have).

Additionally, young children or other people who have never learned how to type at all should learn an optimized layout from the get-go rather than QWERTY. If you are a parent reading this, please don’t inflict uneccessary inefficiency on your child. It certainly doesn’t have to be my layout (Colemak and Dvorak are both more widely available), but at least have them learn something that was actually designed for modern input devices.

Prior Studies of Keyboard Layouts

I suggest you go through the following links (and any of the others from this page that catch your eye – some of the links are dead) before you continue reading my approach, just so you can see what else is out there:

- CarpalX

- MTGAP

- Aus der Neo Welt (AdNW) (and its Google Group)

- The Optimal Keyboard Layout Project (web archived)

- Keyboard Evolve

- Norman

- Workman

- Maltron

There are no doubt other sites out there that discuss these things. I certainly do not pretend to be the first nor most intelligent person that has ever worked on this problem, and wouldn’t want anyone to get that impression. Of the methodology of the sites above, I like AdNW and MTGAP best. I’m planning on writing about all the parameters and a logical weighting scheme at some point. (See the outline above).

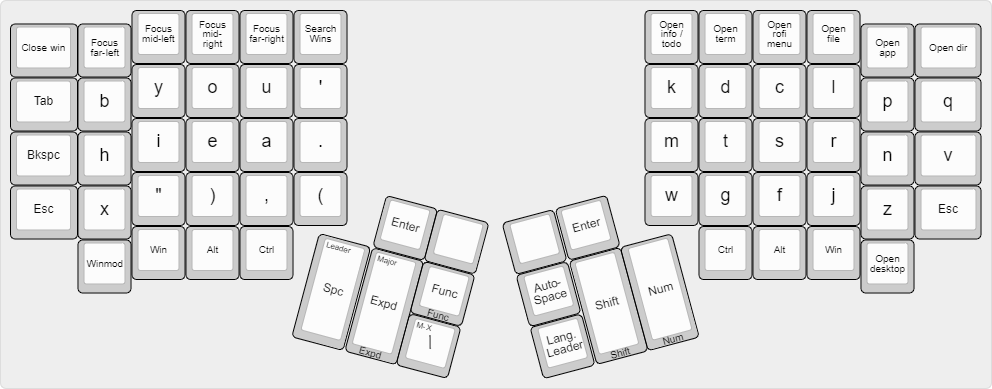

My Layout

My current layout is hosted in this repository.

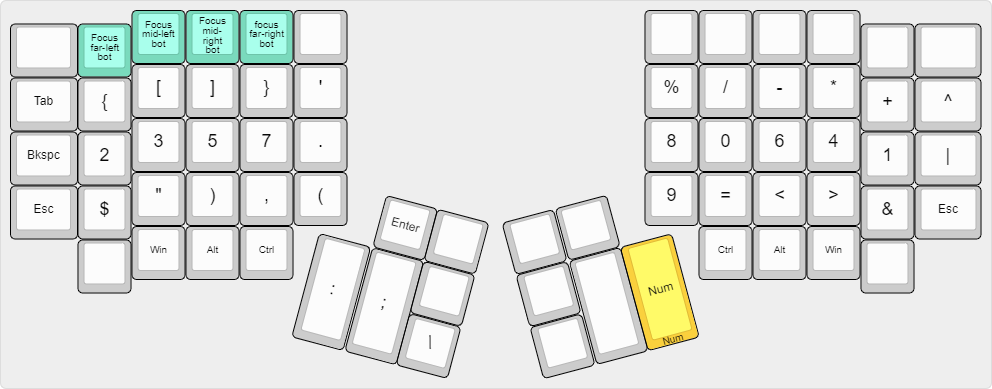

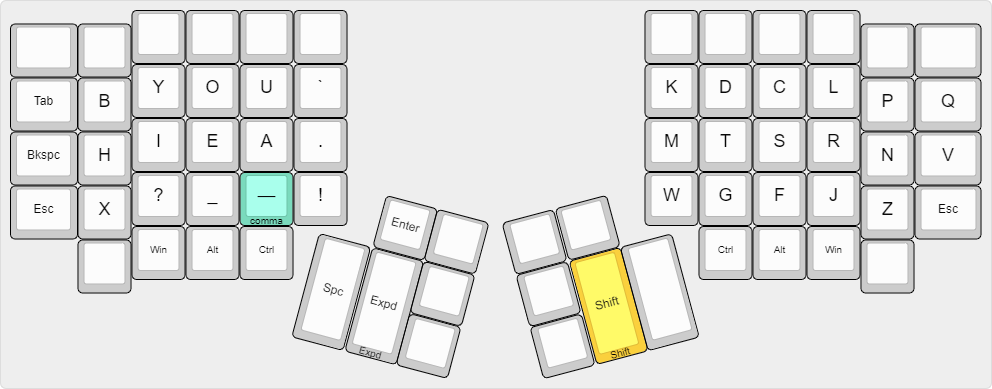

While much thought has gone into the layout, I’m holding off on formally writing it all up until I have enough time to do it properly. Many factors went into the design, such as character frequency, distribution of consonants and vowels in words, leader key versus modifier key considerations, consistency and cognitive load, autospacing and autocapitalization, and so forth. Most all keys are accessible from the combination of the base, shift, and number layers, with only a few infrequently used keys requiring access from a less convenient layer.

Please check back later for a much more thorough explanation of the design. For now, you can have a look at the current plan (some of which has been implemented, some of which has not).

Base layer

Number layer

Shift layer

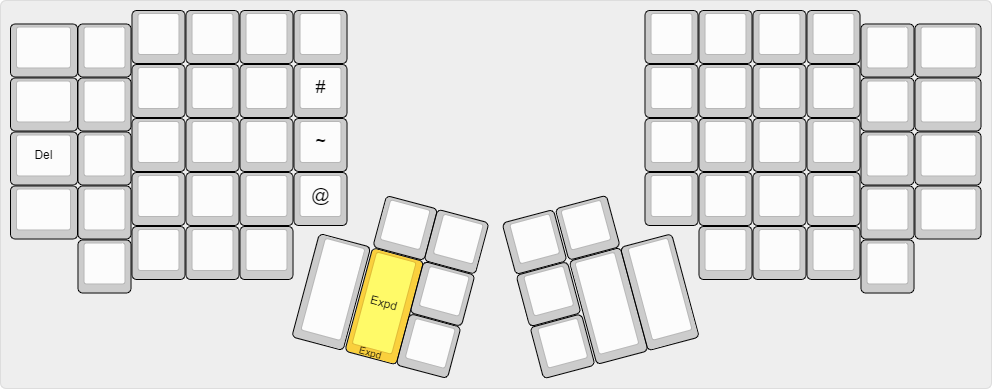

Expand layer

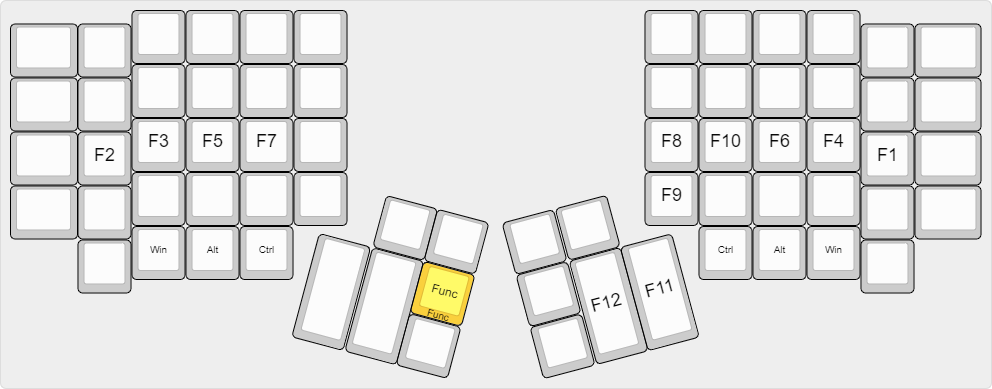

Function-key layer

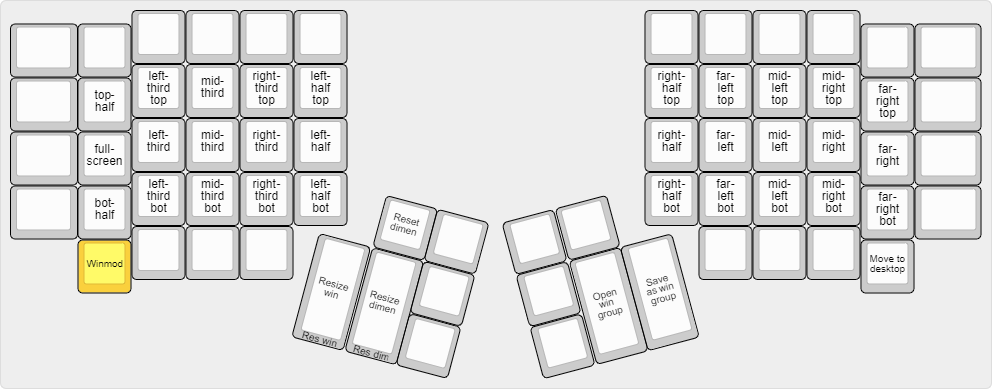

Winmod layer

Virtual desktop layer